Letter about Literature

March 22, 2015

Dear Elie Wiesel,

My parents created and have sustained a secure and comfortable life for me and my brother. In this way I am blessed with privilege. I have never had to worry about the basic necessities of life, or whether I will be denied anything because of my identity. From an early age I was set on the track of education, a path I was eager to walk. Even as a young child I had an insatiable thirst for knowledge which I found most accessible in books. Books have been my favorite lessons and authors my preferred teachers. If a book is in my hands you can forget trying to communicate with me: class is in session and I am in my own world. The most influential book in my private primary education was the Bible. Every day in religion class I heard the most fantastical stories of great adventures and feats performed by God that left me bewildered and excited. I believed every word for its element in the story, so I did not attempt to delve deeper into the context and meaning of these tales.

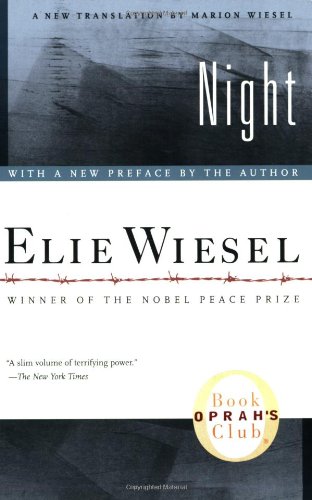

In the eighth grade your memoir Night was a part of the curriculum. Until that point I had lived a relatively sheltered life; I had not given deep thought to the plight of others or known what horrors some faced every day. When I brought your book into my safety bubble I was not expecting more than another stimulating story for the library. I was secure in the faith my parents had taught me, and I thought I was going to read a historical narrative about the Holocaust through the eyes of a Jew. I did not expect that I would learn anything more from the memoir than what I could from my history textbook.

As I read Night the blissful ignorance surrounding my life quickly faded away and a new urgent awareness came to be. My eyes were opened by the intimate details left out of my trusty history textbook. The story had fantastical elements but of a far darker nature. The villains were no longer just goofy words on a page; they were real, tangible, threatening. The classic struggle facing the hero was not easily surmountable but impossibly indestructible. As a girl whose life seemingly revolved around food, I couldn’t begin to imagine the starvation of the body as you described. “Bread, soup – these were my whole life. I was a body. Perhaps less than that even: a starved stomach.” This line sticks with me even today because it also spoke of the starvation of the soul. Unable to reconcile this with my entrenched version of faith I embarked on a religious journey of my own.

After reading your account of life in the concentration camps I grappled with that essential question to faith: how could God allow such atrocity to His people? I was so shaken and confused, I thought the only way to remain faithful to God was to answer it immediately or ignore it altogether. Imagine a twelve-year-old grappling with this huge philosophical debacle. I realized that some relief to my anguish lay in the Bible, just not on the surface. I needed to go deeper into the stories to find the lessons like I needed to be more aware of the outside world.

This confusion ultimately helped me become more grounded in my faith. I know that faith is one that needs to be tested and challenged in order to grow and persevere. When I hear stories of genocide and war I think back to Night. While I may not be any closer to the answer then I was four years ago, I feel confident in my ability to research and question without feeling guilty.

Mr. Wiesel, you were an excellent teacher. Night forced me to open my eyes and to pop my self-concerned bubble. Today I look at the world not as a stream of irrelevant stories, but as people with whom I share a sacred bond of humanity. For these lessons, I thank you.

Sincerely,

Morgan Peck